Spatial Reasoning

A short story

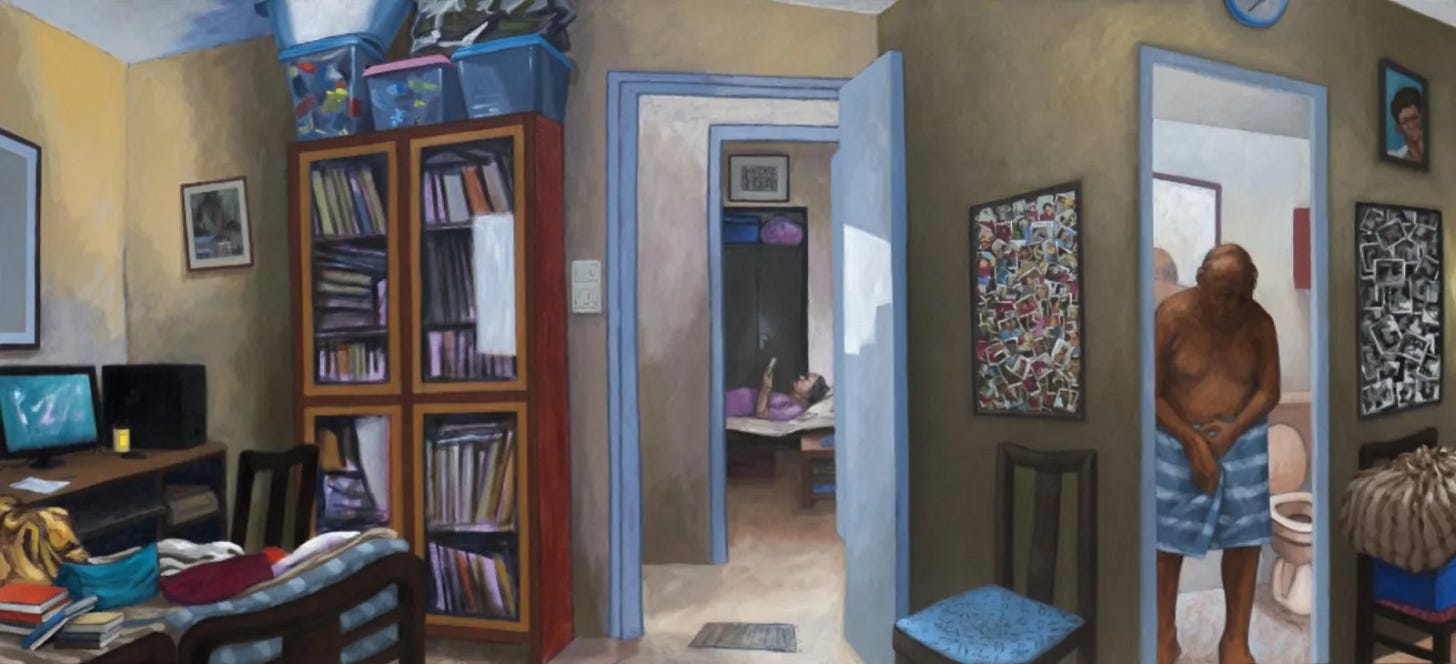

Growing up, the clutter didn’t bother him as much. He hadn’t really formed his view of the world then. He had existed, as most children do, in the ongoing moment, oblivious to the past and the future.

But the clutter was always there. The house had been stuffed with ugly things. When not in use, the TV in the living room, or ‘hall’ as it was called in Bombay, was covered with an embroidered cloth, frayed at the edges. The cloth had little holes, too, made by insects almost invisible to the naked eye. His mother would fold down the fabric to obscure the holes from the front view.

The TV remote had its own covering, a plastic case with purple lining. Despite the care, the lettering on the remote had faded over the years. When it started losing its responsiveness, his father would extract the remote from the case and hit it repeatedly against his open palm. This was an act of resilience and not frustration.

The sunmica-topped dining table had two foldable portions on either flank. The fixed central plank was always loaded with items: a glass vase with plastic rose petals, waxy and dusty; a pen stand whose lacquer had chipped easily; floppy table mats with a low-resolution print of an assortment of fruits. The side flaps would only go up during meal times.

A jumble of steel utensils and plastic containers took up space on the kitchen platform. The adjacent sink was a stone bowl not large enough to accommodate a pressure cooker. Next to it was a pista green fridge, its insides heaving with more stainless steel and smelling of ghee and curdled milk.

After meals, the sink would get clogged with bits of stray tomato and coriander. Sometimes, he would transfer the slimy bits to the brimming rubbish bin, which was lined with a black plastic bag speckled with cucumber peels and the dregs of brewed tea leaves. Two calendars hung from hooks on the wall opposite the sink—one an annual offering from the local optician, the other displaying squiggles of Tamil script and garish images of Hindu gods.

The steel bar in the bathroom was occupied by at least two damp towels: thin and pale white and with a double-lined border in red or green or blue. When he had to dry his hair after a shower, the towels were useless. For that, he would have to sit under the fan in the hall.

So he had grown up amidst this aesthetic of accumulation where things were hoarded not because they were useful but because there was a time when they hadn’t been there at all. In this culture of possession, beauty could only be an afterthought.

He hadn’t given conscious thought to spaces and dimensions before he went to university. In Class Ten, the orthographic and isometric projections in Technical Drawing class had come to him quite naturally. After the Board Exams, his mother took him to a career counselling workshop. He did well on the spatial reasoning test. Father Jeevan, the counsellor whose athletic build couldn’t be disguised by a cassock, told his mother: “He should do architecture. Aptitude is there.”

On his first day in Ahmedabad, a professor showed the class images of her favourite buildings: Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, Ando’s Church of Light, Bawa’s hotel in the forest of Kandalama. He spent the rest of the semester reading about Japanese design and Tropical Modernism. By the end of that semester, he had started thinking of space not as something to be filled, but created. Light became a breathing thing. When he came home for the holidays, he had nothing to say to his parents. He had made the break from their view of the world and things would never be the same again.

He now lives by himself in Goregaon. He is a partner in a boutique architectural practice. He thinks of all this, as he is driven towards Taj Lands End, where his client Zubair Khan is hosting a success party for his new film.

The cars are bumper to bumper on Link Road. As they wait, he spots a patch of mottled light on the footpath, the patterns made by a tall tree inside a building compound. The moment belies the busyness of this road, this city. He rolls down the window and immediately, the muggy air is on his tongue, the sharp stench of Bombay in his nose. It’s a wonder, he thinks, that artists create anything remotely tasteful in this clusterfuck of a city.

Now, in his mid-thirties, he knows that less is attractive only when more is within easy reach. But he hasn’t escaped his origins completely. He is wired to seek balance. It does not sit well with what he considers to be his artistic vision, this idea of balance. Balance is really a middle-class euphemism for limitation.

He remembers the time when he couldn’t stand the sight of that dining table any more. He was home for the holidays on a break between semesters. He had stuffed the fake rose petals in the chipped pen stand and dumped the whole thing in a plastic bin outside the society gate. His insides had glowed with a sense of closure.

When his parents asked, he feigned ignorance. In time-honoured tradition, they put the disappearance down to the maid. I will make her account for it, his mother had said. His mother does not prefer direct confrontation. She has an accusatory tone reserved for such occasions. She would have asked the maid in her special tone, “Manisha, have you seen the pen box on the dining table?”

It is the same tone in which she has been saying things like “I don’t think there is a daughter-in-law in my fate.” He has met a few women at her insistence, but nothing has ‘clicked’, to use her word. Too much water has flowed under the bridges of all these separate lives already. How do you build something new and fresh, especially as the years pass and you become more fixed in your ways?

More traffic on SV Road. The driver turns on the radio. Arijit Singh is singing about an impossible love. Mehfil mein teri, hum na rahe jo, gham toh nahi hai, gham toh nahi hai. His thoughts wander to Maria and what could have been. There is a power in this kind of sentimental music. It makes every driver and passenger a hero in their own tragic film. An image forms in his mind—of Maria kissing his forehead as he lies collapsed in her lap after a trying day. Thank god he has been loved, he thinks. It would be unbearable to go through life without knowing what it feels like.

Kitni daafa subah ko meri tere aangan mein baithe maine shaam kiya. He was both contemptuous and jealous of artists who created things for mass consumption. There was an essential difference between his clients and fans of Arijit Singh. His clients are concerned with art, Arijit’s listeners were thinking about life. There was a whole wide world between that difference.

The car is on Bandstand now. This time he brings the window down to take in a breath of the salty sea air. On his right, he catches a glimpse of ‘Jannat’, his minimalist masterpiece for Zubair Khan. Poetry in stone and brick, Architectural Digest had called it.

His mother calls. “Did you meet her? Her mother just sent me a message. Radhika has been at the venue since 6 o’clock.”

“I haven’t reached, Amma,” he says, not disguising his exasperation, “You need to relax. Why don’t you go for a walk downstairs?”

“Please have an open mind, okay? I am sure you will get along with her. Profession is also the same.”

“Amma, I’m an architect. She is a fashion designer. They are not the same. Listen, does she even know she’s being set up like this?”

Their mothers were part of a WhatsApp group of Tamil ladies in their sixties. They met virtually to sing devotional hymns. Radhika’s mother had posted her daughter’s matrimonial profile on the group, in the chance that someone had an eligible son, or could play matchmaker. She had noted that her daughter was ‘independent-minded’ and worked in a ‘creative field’. It had caught his mother’s attention.

“Of course. She said she knows you by face. When I told Lalitha you’re a good friend of Zubair Khan’s, she said that Radhika has done costume design for his new film. Some things are meant to be.”

“I’m not a good friend of Zubair Khan, Amma.”

“Lalitha told me to tell you she’s wearing a blue dress. You’ve seen her photo. I’m sure you will recognise her. I have shared your mobile number anyway.”

“At least ask before sharing my number with people I don’t know! Okay, I’ve reached. Just entering. Bye.”

The lobby with the giant atrium is milling with people, many of them famous. All of them are heading towards the banquet hall, where Zubair is expected to show up any time. Knowing him, it will be a grand and gimmicky entry.

She is wearing a blue dress, his mother said. Ultramarine blue? Navy blue? The world is full of shades and nuance, but his parents only dealt with monoliths. Maybe it is simpler to live that way. For all his veneration of clean and sharp lines, his mind feels like a ball of wool that will never be unspooled. He can hear the clinking of glasses and snatches of the airy chatter of the rich.

Zubair descends in what looks like a makeshift crane. Was he hiding in the chandelier? The beautiful young women gasp. There is something about this man, a magnetism about his presence. But time has caught up with him too, even the mighty Zubair is no longer frozen in youth.

He spots Radhika near the bar. She has a hooked nose, very aquiline. It adds character to her face. Her hair is pulled back. Her shoulders give off a sheen. An unfamiliar tingle runs down his spine, and causes him to think that anything is possible tonight. He heads up to her, and explains who he is.

“Oh my god, here you are! I promise I wasn’t trying to avoid you. I was just going to call.” She has a husky voice. She seems so sure of herself.

Suddenly, he feels awkward and shifty, like he’s in a place he doesn’t belong. He feels like he’s wearing a mask that is slowly peeling off his face.

“That bhajan group, haan? Quite something. But at least it’s given her something to do.”

“Well, she’s dealing with a Tamil Brahmin girl gone rogue. Maybe desperate measures are warranted.” He’s surprised by how that came out. He’s not had a drink yet.

She guffaws into her cocktail.

“So, architect of Jannat? Zubair couldn’t stop talking about it on set. And you know how it is. When he talks, everyone has to listen. So how come you’re into this whole arranged marriage scene? Broken heart?”

“Well, whose isn’t? I fought the idea when I was younger. Now, there are days when I think it can’t be too bad.”

A glint in her eye, a laugh that takes over her face. “Or—you’re just a good Tamil boy who wants to give his parents a return gift for their long years of sacrifice.”

It is his turn to laugh. He likes her directness. He’s tired of living this oblique life. He can already tell that her rebellion is more resolute than his.

Someone calls out to her from the other side of the bar.

He feels inadequate as he watches the shiny shoulder disappear in a small crowd. Yet, he thinks of a shed by the sea in Ashwem. He will have an upper storey added and make it a home. French windows, a bookshelf that covers the west wall, a red oxide floor for his studio and chessboard tiling for her atelier. Two tasteful Japanese woodblock prints framing the four-poster in the bedroom. They will wear loose cottons and walk around barefoot. They will drink coffee and smoke cigarettes on the little balcony. This is how they will escape the plastic water bottles and clogged kitchen sinks of the generation before theirs.

She is making her way back to him, leading a filmmaker by the hand. He has been in the news recently. He’s adapting a sprawling cop-and-gangster novel for a streaming platform. His jacket sits perfectly on his biceps, his tanned face is crowned by a mop of thick curls. He’s wearing those clear-frame glasses that are so trendy with the creative crowd.

“Meet Abhishek, my boyfriend. I was just telling him what our mothers have been up to.”

They all laugh. Abhishek introduces himself in a cursory way, as if he expects the stranger to know who he is. Someone else joins, allowing herself to be hugged by Radhika even as her hands are occupied by two martini glasses.

The lights shine brilliant in the banquet hall. Her dress is powder blue. Freedom is only temporary. Mothers may not know their children. Their children do not know each other.

Brilliant Vikram! touched a chord.

love the taking down of Van de Rohe and his idiotic quip

“less is attractive only when more is within easy reach.” Profound.