Sometimes, a fully-formed opening line walks into the head. There’s no wrinkle on its bend or sag in its middle. The sentence is so smooth that you must find a story to justify it. Other times, there are scattered thoughts but no words for them. The artist S.H. Raza used to say “How to paint I learnt in France, but what to paint I got from India.” I think about it a lot because every time I know what to write, I’ve forgotten how to. And on days when I feel there’s a grip on style, I don’t know what to say.

This edition of scattered thoughts is courtesy the Netflix show One Day. Based on a book by David Nicholls, the show’s premise is deliciously simple: every 15th July from 1988 to 2007, we enter the lives of Emma Morley and Dexter Mayhew. They are friends, lovers, and much else a man and woman can be to each other over two decades.

This is not a review of One Day. It’s a four-item listicle of things I loved about the show and some memories it sparked about living in the UK. I’m painfully aware of how self-indulgent this kind of content is. But I’m trying to be less precious about genre and ideas of cringe. I’ve finally accepted that there is a thing lazier than maudlin personal writing, and that thing is not writing at all.

(Spoilers ahead. Turn away if you care but then come back after you’ve watched the show?)

Arthur’s Seat

Arthur’s Seat is a volcanic hill in Edinburgh. In the first episode, we see Emma and Dexter climb it after spending a night together (without having sex). Arthur’s Seat looms over the city in a very special way. In 2013, I climbed it along with a cousin. At the top, we took in the panorama and had a sandwich. He told me how locals can squeeze in a bike ride and a hike before the working day begins. That kind of life was exciting and within reach then. I was in the UK as a summer intern at a fancy law firm.

In the 14th and final episode, which is about Dexter trying to grapple with Emma’s sudden death—a plot twist that left me shattered for a few hours—he climbs up Arthur’s Seat again with his daughter Jasmine. This portion is intercut with unseen scenes from his hike with Emma two decades ago. It’s a neat narrative callback. The whole sequence made me feel like I was there. I could taste and touch the years that had passed between Dexter’s assured youth and the burden of his grief.

When they’re climbing down, Emma delivers a long piece about how she’s not interested in accompanying Dexter on his travels or even staying in touch. She comes across as prickly because she’s trying to protect herself—we’ve all been there. She closes with the one thing she really means: “I’m not being a footnote in the story of your life.” The camerawork is fantastic. You see the high blue sky above Emma. The perspective is Dexter’s, and you’re on the hill with them.

And then we cut to a pale and beaten Dexter in the same spot in 2007, looking up at an Emma who isn’t there. The sky is flat. It’s been drained of colour. It’s at that moment that the haunting vocal of Vanbur’s ‘In Cold Light’ kicks in. The track has a bardic quality, kind of like ‘Now We Are Free’ from the final scene in Gladiator.

Dexter’s hair flaps in the sharp wind, and he turns around and follows Jasmine down the hill. It’s only recently that I’ve come to appreciate just how much score and music choices create the conditions for a moment like this. The stomach drops, the heart soars. There’s something in the eye, maybe. It’s so enjoyable to be emotionally manipulated by TV and cinema like this.

A Brimful of Asha

Speaking of soundtracks doing the heavylifting, my heart did a little somersault when I heard Cornershop’s ‘A Brimful of Asha’ at the top of Episode 10 (1997). Emma and her uni gang are getting out of her beat-up car and running up to reach the church where their friend Tilly is getting married.

‘Brimful’, which dropped in 1997, is an inspired choice. In the show, Emma’s parentage is explained as Hindu mum-Christian dad and she’s played by actress Ambika Mod. I can’t pretend to speak authoritatively on the social history of modern Britain, but the sense I get is that ‘Brimful’ was kind of a milestone for the South Asian diaspora. Cornershop, which is fronted by Tjinder Singh and named for a stereotype (the Asian convenience store owner), nailed down the influences of a certain generation of British Asians in ‘Brimful’:

Mohammed Rafi, Lata Mangeshkar, Solid-state radio, Ferguson mono, Bande publique, Jacques Dutronc and the Bolan Boogie, the heavy hitters and the chi-chi music, All India Radio, Two-in-ones, Argo Records, Trojan Records

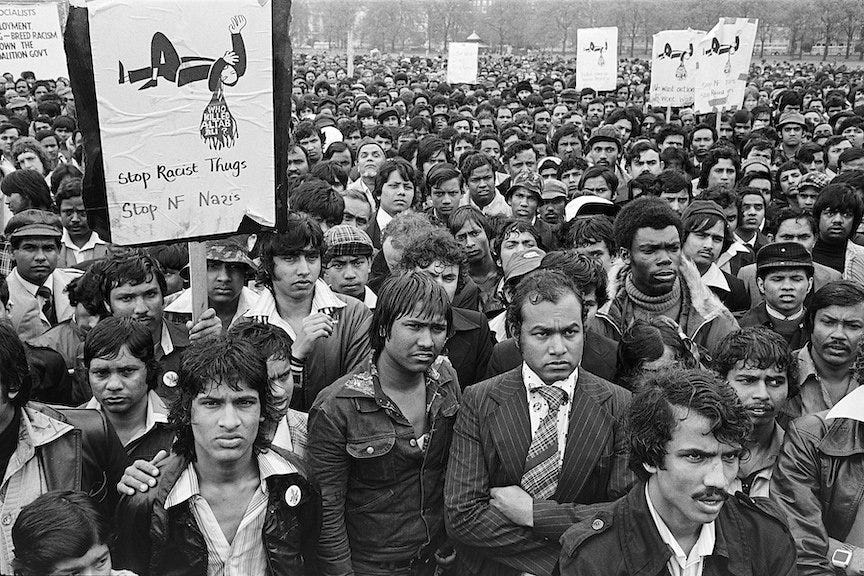

It was a generation that was making its presence felt in the British arts establishment. Two years before ‘Brimful’, the Asian Dub Foundation had released ‘Rebel Warrior’, which opened with a stirring rendition of lines from Kazi Nazrul Islam’s poem ‘Bidrohi’. The music video has shots of Bengali children in long-sleeved shirts and trousers playing football in the courtyard of what looks like an East London council estate.

This was the music I was listening to on weekends in 2015, as I walked down Whitechapel High Street in London after dropping my suits at a laundry near the tube station. On the pavement, bearded men sold mangoes by the crate and chillies by the fist. I don’t think they pined for their Sylheti childhoods as a generation before might have. Their bonds with Bangladesh were very much alive through annual trips and LycaMobile SIM cards.

Whitechapel didn’t really remind me of home. It was a creation of its own place and time, and I went there for the cheap laundry, a favourite pub and to feed my curiosity about the British Asian experience. I also went there for the small wonder of being able to see the gleaming glass towers of the City in the distance. On weekdays (and occasionally weekends), I worked as a lawyer in one of those buildings.

On one of my early walks in Whitechapel, I crossed Altab Ali Park, named for the 24-year-old who’d been murdered in 1978, during a time of high racial tensions. Slowly, I began to understand the wider universe of ‘Rebel Warrior’ and ‘Brimful’.

All this came rushing back when I heard those bars of ‘Brimful’ in One Day. Great art has a way of trapping a prolonged moment in national history in a throwaway manner.

Later in the episode, during the wedding toast, Emma calls Tilly’s union with Graham the “finest Grantham meets Grenada mash-up the world has ever seen.” And there, I think, lies quite another story about multicultural Britain, about the children of the Windrush generation mingling with and marrying people whose families have lived in the same market towns of England for hundreds of years.

Now, god knows race relations in Britain have been fraught AF. And I know that One Day is decidedly not about race (in the way it is about class, for example). But my point is to say that to imagine Britain as anything other than many-coloured requires a wild imaginative leap for even the staunchest neo-imperialist. Segregation is a cold fact in the UK and it stared me in the face when I went looking for it, but it co-existed with the possibility of integration. Tilly and Graham, Emma and Dexter—they represent that possibility.

Episode 5 and the train station bridge

In Episode 5 (1992), a badly hungover Dexter spends the day at his parents’ home in Oxfordshire. His mother is severely weakened by cancer, and he must carry her up the stairs to put her into bed. Fatigued by liquor, drugs and despondency, he lies down on the bed in his childhood room.

When he wakes, mid-morning has become late evening and his father is livid that Dexter has wasted the day because of the state he is in. It’s an affecting 15 minutes of television—we see mother, father and son grapple with the finality of their lives never being the same again. One person’s disease has eaten into three dispositions. Love and fealty endures but it comes with a sediment of resentment that hangs heavy during the life of the sick person.

We see Dexter standing forlorn, outside the red-brick facade of a deserted Radley station. He takes the foot-over bridge to reach a pay phone on the opposite platform. He leaves Emma many messages, but she’s left her apartment to get to a date. It’s a staggering performance by the actor Leo Woodall. His sniffles and sobs are stifled, a shudder is seemingly involuntary and he clutches his chest in a way that somehow doesn’t come across as hammy.

And then there’s a money shot, taken from the foot-over bridge. It’s late on a summer evening in countryside England. I’d put it at 8.30pm. Green trees on either side, not a soul on the platforms. And we see Dexter bent over, holding his knees, trying to keep his balance.

This scene spoke to me because it showed a child grappling with a parent’s disease and his own slackening grip on the narrative he had created for his life.

It also stuck because of the preciseness with which it evoked a train station on a British summer evening. I used to love the ritual of train rides in the UK. The ticket with the orange bands on top and bottom, a Cornish pasty and a packet of crisps, the hushed voices and comfortable seats. And from the window—predictable, manicured country. I’d be so absorbed in the showreel of my own protagonist (the solitary-dutiful-charming young man abroad, meaning myself) that I never thought that the houses and platforms we were speeding past could be hosting their own dramas. Maybe the party boy sitting next to me on the 20.19 from Oxford was struggling to come to terms with a parent’s illness.

Emma/Ambika and Dexter/Leo

I’ve been marvelling at how the character arcs play out over the 14 episodes. Emma: I feel like I know her well. Some of it has to do with her ethnicity, but I found it easy to map her onto people in real life. The cutting sarcasm, bookish brilliance and insecurities of the early 20s; the coming into her own in the 30s, on the back of professional, sexual, romantic success. And through it all: the easy empathy, the solid female friendships, the determination to build beautiful lives, homes and safe spaces in a world of emotionally stunted men. Ambika Mod, you lived Emma!

Dexter, too. Nicole Taylor, who headed the writer’s room, told The New York Times that she didn’t want to make him an “archetypical posh boy” but wanted to emphasise his vulnerability. And Woodall does a fantastic job of translating how a man can go from cocky lad who’s constantly thinking about his next lay to a grief-stricken father. I came across a few tweets that said that the makers dragged out the last few episodes but I loved them for what they do with Dexter’s character.

There’s a scene on a bridge in Paris, where Dexter goes to meet Emma in the middle of his divorce. When he says that everything seemed possible when he was younger and nothing seems possible now, Emma, looking very chic and every bit put together, rubs his arm and says “You’ve just lost your confidence, that’s all.”

That hit hard, and home. How does a dude who swaggered bare-chested on a beach in Greece, glistening with youthful vitality, become a jaded man who’s somewhat in touch with his emotions? And how does this phase often coincide with the period when the women in his peer group are living their fullest, most authentic lives? It’s one of modern masculinity’s interesting questions, and a great leveller of our times.

End notes:

This Substack recently crossed 100 subscribers! I hope this will seem like a small number one day, but right now, it feels very big. A massive thank you to everyone who subscribed, shared, commented or sent me a message saying they enjoyed reading something I put out. I always write to be read, so it means everything.

Also, thank you to my friend J, who messaged asking if I had “seen/heard of One Day on Netflix.” I hadn’t. She asked me to look up the lead actress because she resembles someone we both know. I tried to guess but it took me a couple of clues to get right. Then I watched One Day and now Ambika’s Emma reminds me of many people I know and have known.

I liked the show but enjoyed this post much more!

I loved the show and your post made me love it a bit more.